Jesuit ballet character Fire

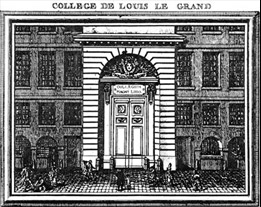

The Jesuit college of Louis le Grand, where Charles lives and works. The arches to the right of the doors are shop entrances.

The Grand Châtelet, both a prison and law courts, where Lieutenant-Général La Reynie has his office.

The 17th Century

Watch parts of L'Esperance, performed at Louis le Grand in August 1709, restaged by Judith in San Francisco in May 1985, and brought back to Louis le Grand on the screen, on May 25, 2013! (Jesuit ballets were not danced in churches, but I chose this setting for L'Esperance because it provided some architectural background, as the original sets would have.)

Dance: A mystery within the Charles du Luc mysteries?

A lot of people dance in the Charles du Luc historical mysteries--onstage and socially--and the dancing is part of the novels' plots. In Charles's France, knowing how to dance well was important socially, and also in relation to power and politics. Dance was important to a degree hard for us to understand. So Jesuit teachers like Charles really did produce ballets for their students to dance in. No, not giant toe-shoes and tutus. Think Louis XIV and his fabulous wardrobe, lots of waving plumes in your hair, and high heeled shoes. Jesuit ballet used what's called baroque dance technique--the dance style used from about 1660 to 1760 or so. To see what it looked like, (as done by the brilliant New York Baroque Dance Company), click here

Who were the Jesuits?

They were, and still are, members of a Roman Catholic religious order for men called The Society of Jesus, founded in 1540 by St. Ignatius of Loyola.

So, why were the Jesuits doing this?

They made ballets because they cared about art and communication, and communication meant body as much as it meant words. In France in those years, if you didn't know how to dance, and dance well, you were nobody going nowhere. Dancing at Louis XIV's court meant that just you and your partner danced while everyone else watched. Being a good dancer was so important, that when a cocky young guy messed up on the ballroom floor, his father had to send him abroad till the scandal died down.

The Jesuits ran schools for boys and taught them Rhetoric. Rhetoric was the art of public communication with body and voice. Performing in ballets gave the Jesuits' students strong, eloquent bodies and trained them to dance well at court and everywhere else. So their fathers wouldn't have to send them abroad when they messed up...

Charles's Paris

Sometimes at book signings, a reader comes through the line with a map of Paris and tells me about looking for the places Charles goes in the books. I do that, too, when I read historical fiction. And if the setting is a well-known place, I want to know how it was different in the time of the story.

When someone says "Paris," what do you see in your mind? The Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, Notre Dame, the Champs Élysées? The endless treasures in the Louvre Museum and the equally endless line of tourists waiting outside? The Luxembourg Gardens, the Paris Opera, sidewalk cafés, the small, distinctively shaped street signs? When someone says "Paris," I see all those things in my head. But Charles didn't. Eight of those nine familiar images weren't there--or weren't there as we know them--in the 1680's.

Only Notre Dame was there more or less as we know it. As for the Louvre, it was a palace, not a museum. The Luxembourg Gardens were the private grounds of a palace and a monastery. There were no sidewalk cafés--cafés were just beginning and the only sidewalk was on a bridge, the Pont Neuf. There no street signs or Champs Élysées until the 18th century. The Eiffel Tower, the Paris Opera, and the Arc de Triomphe were built in the 19th century.

What was there in Charles's time? What did he see that we no longer see? The old city walls were being torn down, but much of medieval Paris still existed. The Knights Templar commanderie still stood north of the river. There were twenty-one churches--besides Notre Dame--on the Île de la Cité alone, and medieval houses and shops were a normal part of the cityscape. All bridges except the Pont Neuf were lined with four and five story houses. The old public gallows north of the city--which could hang sixty felons at once--wasn't much used. But public executions still took place outside the medieval Hôtel de Ville, the town hall, beside the Seine. The Seine had three islands then, instead of the two we know. The little Île Louviers, used as a wood-yard, was east of the Ile St. Louis.

But Paris was also changing in Charles's time. There was steady rebuilding in brick and stone, leading some people to call Paris "the new Rome." Most streets were paved and many were being widened--one to an astonishing forty feet! The public sewer system was slowly expanding, but some of its ditches were still open to the air. The river still had a few stretches of natural bank as it flowed through the city, but most of it was already lined with quays.

In the 1680's, Paris had between four and five hundred thousand people. But the city within the old walls was small. If you walked south from the Seine on the Left Bank's rue St. Jacques, the distance to the wall was about 10 modern city blocks. The Right Bank stretched much farther east and west than the Left, but if you walked north from that side of the river to the old line of the wall, the distance was about 20 blocks. There were suburbs--faubourgs--all around the city, but they still included large stretches of farmland, woods, and gardens. What's now Père La Chaise cemetery was out in the country, and Montmartre was a tiny village away to the north, on a hill dotted with windmills.

The Paris Charles saw from his window on his first night at the Jesuit college was not our Paris. But it was a city already very old, and I think that when "he kissed his hand to sleeping Paris," he felt its mysterious magic.